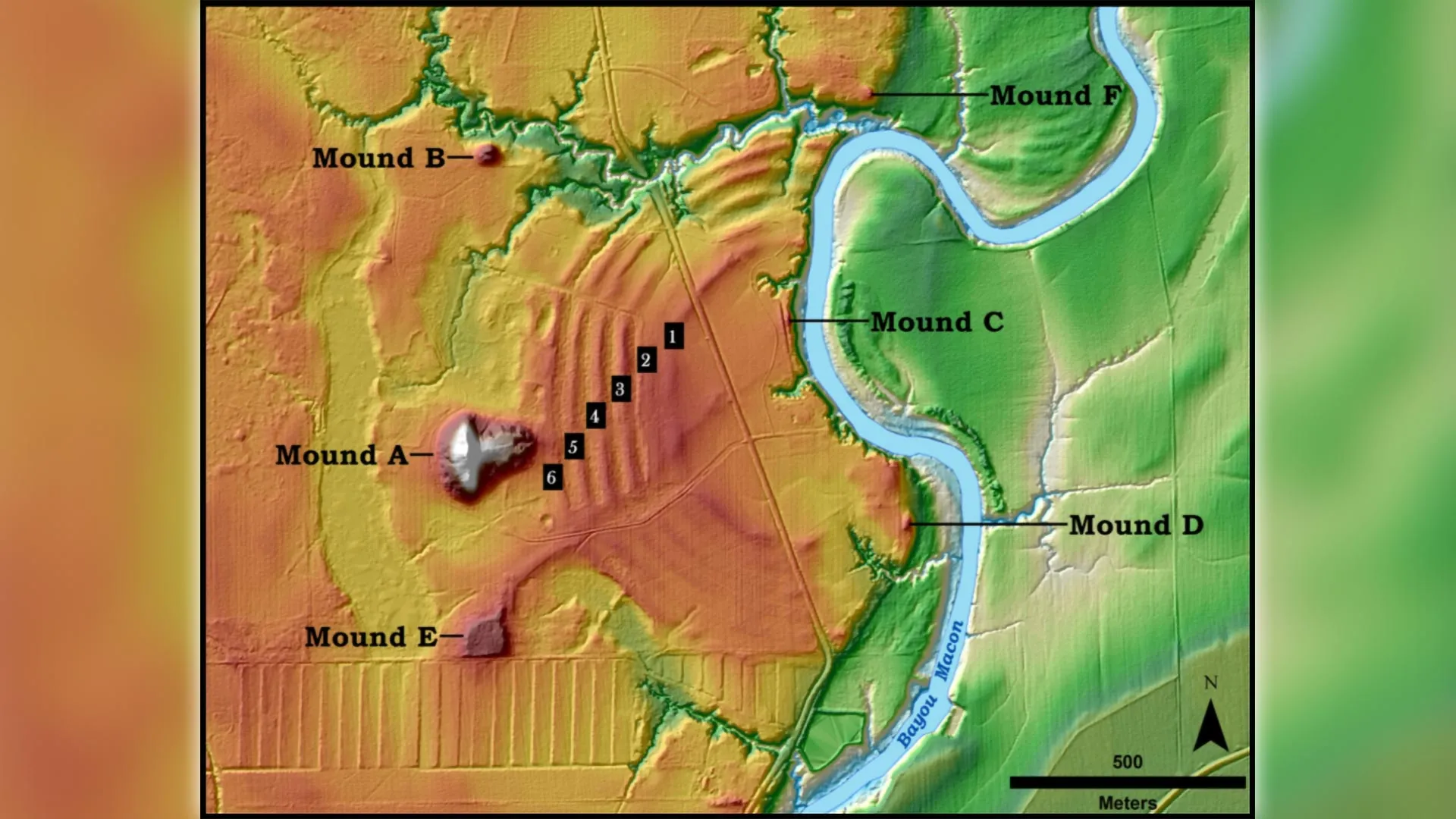

The diagram presented here illustrates the primary elements of the Poverty Point archaeological site situated in northern Louisiana. To the right, the green expanse represents the floodplain of the Mississippi River. The orange region indicates Macon Ridge, which serves as the elevated terrain where the site was established. Observably, six C-shaped ridges form a distinctive feature of the location. Certain sections of these ridges have suffered damage due to both historical and contemporary human interventions. The patterned area located south of Mound E stems from agricultural operations conducted over time. Numerous low-lying zones surrounding the site, depicted in lighter yellow hues, are interpreted by experts as locations from which soil was extracted to construct the ridges and mounds. Credit: T.R. Kidder

Origins of Monumental Earthworks at Poverty Point

Roughly 3,500 years in the past, groups of hunter-gatherers initiated the formation of vast earthen structures positioned along the banks of the Mississippi River at Poverty Point, an esteemed UNESCO World Heritage Site located in northeastern Louisiana. Tristram “T.R.” Kidder, who holds the position of Edward S. and Tedi Macias Professor of anthropology, characterizes the immense scope of this endeavor in vivid terms: “Even taking a conservative estimate, these ancient inhabitants relocated approximately 140,000 loads of soil equivalent to those carried by modern dump trucks, achieving this feat entirely without the aid of horses or wheeled vehicles. The labor involved was extraordinarily demanding. The central puzzle remains: what drove them to undertake such a colossal project? What inner motivations propelled this extraordinary effort?”

Kidder, along with his research team from the Arts & Sciences division at Washington University in St. Louis, revisited Poverty Point and a selection of adjacent sites to gather fresh radiocarbon dating samples and to meticulously reassess the existing archaeological materials. Their latest investigations are steering them toward perspectives that challenge and diverge from the longstanding conventional understandings of how these prehistoric societies were structured and operated.

Kidder has elaborated on these discoveries through two recently published scholarly articles in the journal Southeastern Archaeology. These works were co-authored with his graduate student, Olivia Baumgartel, and Seth Grooms, who earned his PhD from WashU in 2023 and is now affiliated with Appalachian State University.

Traces of Extensive Trade and Travel Networks

Poverty Point has long been celebrated for its enormous mounds, many of which are still prominently visible in the contemporary landscape. However, the smaller artifacts unearthed at the location reveal an equally compelling narrative. Excavations have yielded thousands of clay balls that were evidently fired for cooking purposes, alongside exotic materials transported from distant locales. These include quartz crystals sourced from regions in Arkansas, soapstone originating from the vicinity of Atlanta, Georgia, and copper-based decorative items that trace their origins to areas proximate to the Great Lakes. “These ancient peoples engaged in extensive trading activities and undertook journeys spanning vast distances,” Kidder observed.

For decades, academic consensus held that the erection of Poverty Point’s monumental features necessitated a rigidly organized society characterized by hierarchical leadership, with labor coordinated across multiple generations. This assumption drew parallels from the later Cahokia Mounds complex in present-day Illinois, which emerged under a chiefdom governance model. Researchers projected a similar organizational framework onto Poverty Point. Nevertheless, Kidder cautions that the most straightforward hypothesis does not invariably prove to be the accurate one, urging a reevaluation of preconceived notions.

Redefining Social Dynamics at Poverty Point

In their latest scholarly contribution, Kidder and Grooms advance an alternative conceptualization of Poverty Point’s societal framework. They posit that rather than functioning as a fixed residential hub directed by authoritative figures who marshaled compulsory labor forces, the site operated primarily as a grand convocation point. Here, individuals hailing from diverse communities across the southeastern and midwestern United States convened at regular intervals to exchange goods, engage in festivities, foster alliances, and partake in collective ceremonial practices.

These propositions build upon conceptual frameworks that Kidder and his graduate students have been refining over an extended period. Drawing from the corpus of archaeological data, they depict a society bound together by a shared sense of mission and communal ethos. As Baumgartel articulates, “Our analysis supports the notion that these were egalitarian societies of hunter-gatherers, operating without subjugation to a dominant ruling elite or chiefdom structure.”

Kidder further contends that the architectural earthworks do not serve to commemorate or elevate a privileged class of elites. Instead, he interprets the mounds as emblematic of a collaborative communal initiative, executed across a span of several years, as participants endeavored to exert influence over an environment fraught with unpredictability and peril. “During the era when these earthworks were under construction, the southeastern United States experienced frequent episodes of extreme weather phenomena and devastating inundations,” he explained. “Our hypothesis is that the builders of Poverty Point erected these mounds, conducted elaborate rituals, and deposited precious artifacts as sacrificial offerings imbued with spiritual significance, aimed at propitiating the unpredictable forces of nature.”

A Sacred Terrain Devoid of Lasting Habitation

Kidder and Grooms underscore a critical observation: despite extensive investigations, archaeologists have yet to uncover any burials or remnants indicative of permanent domestic structures at Poverty Point. “Such discoveries would be anticipated in a site that served as a continuously inhabited village over prolonged periods,” Kidder remarked. “The traditional model positing continuous occupation at Poverty Point spanning centuries has progressively eroded under scrutiny, necessitating the development of an entirely new interpretive paradigm.”

While the ephemeral nature of spiritual practices rarely manifests in durable physical remnants like ceramics or implements, Kidder and Grooms marshal persuasive evidence to affirm the site’s profound religious import. “Over many years, I have engaged in extensive dialogues with individuals of Native American descent,” Kidder shared, highlighting that Grooms belongs to the Lumbee tribe from North Carolina. These exchanges have bolstered their conviction that the assemblies at Poverty Point were propelled by sacred imperatives that transcend contemporary Western paradigms centered on economic or materialistic incentives.

“As practitioners of archaeology, we must cultivate openness to diverse modes of cognition and worldview,” Kidder emphasized. “The prevailing Western perspective assumes that such arduous long-distance travels and laborious constructions would only occur if participants reaped tangible economic benefits. In contrast, we propose that these ancient peoples were driven by a profound moral imperative to mend and restore a cosmos perceived as fractured and in disarray.”

Diverse Chronologies of Regional Gathering Sites

Poverty Point was far from the sole prominent assembly location in this geographic sector of North America. Researchers from Washington University are concurrently investigating two additional significant sites—Claiborne and Cedarland—located in western Mississippi, both of which once harbored impressive assemblages of artifacts comparable to those at Poverty Point. Regrettably, these locations have endured substantial disruption from modern developmental projects and the illicit extraction of artifacts by private enthusiasts. “It is a regrettable reality of contemporary archaeology that investigations often lag behind the destructive advance of heavy machinery like bulldozers,” Kidder lamented.

To minimize additional disturbance to these sensitive areas, the research team employed non-invasive methods, including radiocarbon analysis on clam shells and deer bones that had been gathered approximately 50 years prior. The resultant data reveal that Cedarland predates both Claiborne and Poverty Point by around 500 years, establishing a unique temporal profile for each site. Baumgartel summarized their findings succinctly: “Through rigorous analysis, we have disentangled these sites, ascribed independent historical trajectories to them, and begun to elucidate the mechanisms by which artifacts originating from widespread regional sources converged at these locations.”

Ongoing Fieldwork and Prospective Revelations

This methodical investigative strategy persists at Poverty Point itself. In the months of May and June of the current year, Kidder and Baumgartel resumed excavations at test trenches initially dug during the 1970s. Leveraging cutting-edge radiocarbon dating protocols alongside sophisticated microscopic analytical tools, they seek to extract insights inaccessible to prior generations of scholars.

“Olivia and I dedicated considerable time to sifting through minuscule quantities of earth, under sweltering and exhausting conditions,” Kidder recounted. “Reflecting on the monumental exertion expended by the original inhabitants of Poverty Point to fashion those earthworks fills me with awe. Their legacy continues to motivate and inspire our ongoing pursuits.”

The implications of these findings extend far beyond the immediate context of Poverty Point, inviting a broader reconsideration of how prehistoric societies in the Americas navigated environmental challenges through communal and spiritual means. By integrating new chronological data with ethnographic perspectives, researchers are painting a richer portrait of egalitarian networks that spanned continents long before the advent of formalized states or empires. This evolving understanding not only reshapes our knowledge of ancient Louisiana’s mound-building cultures but also highlights the enduring human capacity for collective action in the face of existential threats posed by nature’s volatility.

Future excavations promise to yield even more granular details about the daily lives, trade routes, and ritual practices of these resilient hunter-gatherers. As analytical technologies advance, so too does our ability to peer deeper into the motivations that drove these monumental constructions, offering timeless lessons on community, spirituality, and adaptation in precarious times.